Jefferson County, Mississippi

Jefferson County, MississippiA Proud Part of the Mississippi GenWeb!

Contact Us:

State Coordinator: Jeff Kemp

County Coordinator: Gerry Westmoreland

If you have information to share, send it to Jefferson County MSGenWeb.

In the menu on the left there is an index of Historic Records on our website.

Special thanks to: Sue B. Moore for finding this book and to the

University of North Carolina - Chapel Hill Libraries for the use of

the material for research purposes.

© This work is the property

of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. It may be used

freely by individuals for research, teaching and personal use as

long as this statement of availability is included in the text.

Call number 973.78 M78r 1901 (Davis Library, UNC-CH)

REMINISCENCES OF A MISSISSIPPIAN

IN PEACE AND WAR:

Electronic Edition.

Frank Alexander Montgomery, b. 1830

FRANK A. MONTGOMERY

Lieutenant-Colonel First Mississippi

Cavalry, Armstrong's

Mississippi Brigade; Member of Legislature,

1880, 1882, 1884, 1896,

and one term Judge of Fourth Circuit

Court District of Miss.

CINCINNATI

THE ROBERT CLARKE COMPANY

PRESS

1901

Page verso

COPYRIGHT, 1901, BY

FRANK A.

MONTGOMERY

Press of The Robert Clarke Co.

Cincinnati, O.,

U.S.A.

Dedication

To my surviving comrades of

Armstrong's Old Mississippi Cavalry Brigade

and to the memory of

its gallant dead

I dedicate this book.

Page vii

PREFACE.

Most people who read books look first at the

Preface to see what the author has to say about himself or about his

book, and often this contains an excuse for writing it. I have no

excuse to offer for what I have written, and since the book itself

is an autobiography will here say nothing about myself; but I think

it proper to give some of the reasons which have induced me at this

late day to become an author.

Most people who read books look first at the

Preface to see what the author has to say about himself or about his

book, and often this contains an excuse for writing it. I have no

excuse to offer for what I have written, and since the book itself

is an autobiography will here say nothing about myself; but I think

it proper to give some of the reasons which have induced me at this

late day to become an author.

It has been my fortune to

have lived for seventy years in my native state, Mississippi, and

until within the last few months to have led an active life from

boyhood to my present age, never without some occupation which was

congenial to me. But time which has brought me age has also brought

me leisure, and I have availed myself of it to write my

recollections of so much of the war between the states in which my

own immediate cavalry command took part. In the following pages,

however, I have not confined myself to this, but have allowed my

memory to carry me back to the days when I was a young man, and to

speak of Mississippi life as it then was. So also I have dwelt upon

the reconstruction era in the state and brought my memoirs down to

the present time, with, however, only a passing reference to the

civil offices I have held.

Page viii

So far as

the war is concerned I have felt it almost a duty, it certainly has

been a pleasure, to recall the incidents of that stirring time and

to rescue from oblivion, as far as I can, the names and deeds of

some Mississippi soldiers, and commands, to whom history in the

state has done but scant justice.

If I have succeeded in

this, if I have contributed, in ever so slight a degree, to the

history of the state or of the war, I will be amply repaid for the

work I have done.

FRANK A. MONTGOMERY.

Page ix

CHAPTER I.

Introduction--Birth place--Old Natchez

trace--Lost villages of seventy years ago--Territory of

Mississippi--Ancestors--Country school--Oakland College--Its

president--His lecture one day--Political speech of Dr. Duncan, of

Ohio--Whig party--Excitement in Mississippi in 1851--Senators

Jefferson Davis and Henry Foote--Speeches by them--Tragic death of

Dr. Chamberlain--Fate of Oakland College. . . . .

CHAPTER II.

Mexican war--Jefferson troop--General Thomas Hinds--Natchez

fencibles, Captain Clay--Vicksburg--Mustering officer, General

Duffield--Company rejected--Trip to Jackson--Governor Brown--General

McMackin--Alleghany College, Meadville,

Pennsylvania--Concert--Escaped slave--Copper cents--Skating, sleigh

riding--Militia muster--Home again--Cotton planter of those

days--The negro as he then was--As he is now. . . . . 12

CHAPTER III.

Railroads--Shinplasters--Customs of the

times--Barbecues--Camp meetings--Militia drills--Shooting

matches--Music of the times--The preacher and the

robber--Indians--S. S. Prentiss--Dueling. . . . . 22

CHAPTER IV.

Marriage--Move to Bolivar county--Old town of Napoleon--The

hunter--Money--State banks--Overflows and levees--Battle of

Armageddon--John Brown's raid--Effect on the south--Election of Mr.

Lincoln . . . . . 29 Page x

CHAPTER V.

Excitement--Elections before the war--Formation of

companies--Bolivar troop--Secession of the state--Mississippi a

nation--Army and custom houses--General Charles Clark--Anecdote . .

. . . 37 CHAPTER VI.

Trip to New Orleans--Company in camp--An

old soldier's popularity and final fate--Take company to

Memphis--Roster of company--General Pillow--General William T.

Martin--Anecdote--Whether negro or white man--Life depended on the

question--Ordered to Union City . . . . . 44

CHAPTER VII.

General Frank Cheatham--First Mississippi Cavalry Battalion, Major

Miller--General Cheatham's staff--Battle of Manassas, war

over--Occupation of New Madrid--Brigadier General M. Jeff. Thompson,

Missouri State Guard--His army--Evacuate New Madrid--Return next

day--Scout to Charleston--Lose a man, captured--Great excitement at

home over this--Hickman, Kentucky--Gunboats--Captain Marsh Miller

and the Grampus--Columbus, battalion increased. . . . . 53 CHAPTER

VIII.

Gunboats and Grampus--Ordered with squadron to

Belmont--Colonel Tappan in command--Watson's Battery--Old college

mate--Dashing poker player of old times, one of the

Watsons--Scouting--First fight--Federal sergeant killed--Leave of

absence, battle of Belmont--Winter quarters--State troops under

General Alcorn--New orderly sergeant--Old acquaintance from

California--Runaway negroes--Detailed on recruiting service--Battle

of Shiloh--Battalion increased to regiment--Colonel Lindsay in

command--His habits--army falls back to Tupelo. . . . . 63 CHAPTER

IX.

Reorganization of regiment--Report to General

Villipigue--Ordered to Senatobia--Jeff. Thompson again--His Indian

army--Mrs. M. Galloway, of Memphis--Ordered to Bolivar Page xi

county--Captain Herrin Reports to me--Fights with General Hovey in

Coahoma county--Congressman Hal. Chambers--His duel with Mr.

Lake--Fight at Driscoll's gin--Rejoin regiment. . . . . 74

CHAPTER X.

Brigaded with Colonel W. H. Jackson, Tennessee

cavalry--Brigadier-General Frank C. Armstrong--Raid into

Tennessee--Fight near Bolivar--Death of Lieutenant-Colonel Hogg, of

Federal cavalry, his gallant charge--Attack Medon, repulsed--Battle

of Denmark or Brittain's Lane--Severe loss--Captain Beall's

presentiment and death--Gallant charge of Colonel Wirt Adams--His

unfortunate fate after the war--Back in Mississippi--Move towards

Corinth--Rout Federal cavalry at Hatchie river--Colonel Pinson

wounded--General Van Dorn's advance on Corinth--Battle of

Corinth--Raid around Corinth--Narrow escape--Van Dorn's retreat--In

the rear--Back to Ripley. . . . . 84

CHAPTER XI.

Army at Holly

Springs--General Pemberton--Fight with Grierson in Coldwater

Bottom--two nameless heroes--Old Lamar, enemy advances--Evacuation

of Holly Springs--Report to General Pemberton at Jackson--General

Gregg of Texas--Trouble with General Jackson--Correspondence with

General Pemberton and secretary of war--Grenada, court

martial--Charges preferred by General Jackson--Acquitted and ordered

back to the regiment--President Davis reviews army at Grenada. . . .

. 96

CHAPTER XII.

Columbia, Tennessee--General Forrest--Van

Dorn--Sick leave--Faithful servant Jake Jones--Cross delta in dug

out--Methodist preacher and his wife--Lost for day and

night--Home--"Featherbeds"--Anecdotes--Fight of "Featherbeds" at my

place--Houses all burned by Federals--Privations of the

people--Return to army--Incidentals of trip--Rejoin regiment at

Mechanicsburg. . . . . 111 CHAPTER XIII.

General

Cosby--Skirmishing--Letter to wife--Son of General Thomas

Hinds--Letter to wife 4th of July, 1863--General Page xii

Joseph

E. Johnston, move to relieve Vicksburg--Brigade ordered forward to

the attack--Surrender of Pemberton--Fall back on

Jackson--Confederacy cut asunder--How General Dick Taylor crossed

river--Effect of fall of Vicksburg--Pemberton blamed

severely--Loyalty doubted--siege of Jackson--Evacuation of

Jackson--Judge Sharkey--"Camp near Brandon"--Letters to my

wife--Captain Herrin's dash at Federals--Captain Herrin captures

foraging party--Lightning kills man in camp--scout into Jefferson

county, General Clark--"Count Wallace". . . . . 122

CHAPTER XIV.

Camp near Lexington--Colonel Ross' Texas regiment--Camp near

Richland--General Reuben Davis, candidate for

governor--Anecdote--New issue and old issue, Confederate

money--Assault on sutler's tent--Letter to my wife--Presentation of

flag--Ross' Texas and First Mississippi regiments move to Tennessee

valley--General Sherman advancing through valley to

Chattanooga--Fights in the valley--Adjutant Beasly killed--Ordered

back to Mississippi--General Stephen D. Lee in command--Night march

after Federals, skirmish--Battle at Wolfe river near Moscow--Severe

loss in regiment and by Federals. . . . . 135

CHAPTER XV.

Opening of the year 1864--Gloomy prospects--General Sherman's march

through Mississippi--Skirmish on Joe Davis' place--Sharp Skirmish at

Clinton--Jackson, driven through place--Enter Meridian--Ordered to

reinforce Forrest--Forrest victorious, and ordered back to follow

Sherman--Fight near Sharon--Scout toward Canton, capture foraging

party with wagons--Another fight on road from Sharon, with loss--In

camp near Benton--Colonel George Moorman--Colonel Pinson goes home

and marries--Ordered to Georgia--General Frank C. Armstrong in

command of brigade--Letter from him. . . . . 148

CHAPTER XVI.

March to Georgia--Campaign in Georgia--Join General Johnston at

Adairsville, engaged at once--Letter to my wife from

Cartersville--Constant fighting--General Johnston's battle order,

Page xiii

enthusiasm of troops--Cross the Etowah, brigade in

rear--Fight at creek--Soldier's dream--Battle of Dallas, assault

Federal intrenchments--Repulsed with severe loss in regiment and

brigade--Letter to my wife describing the battle. . . . . 160

CHAPTER XVII.

Lost Mountain, constant fighting--General Polk

killed, regret at his death--Armstrong's scout to the rear, destroys

railroad and captures prisoners--Returns to army and orders me to

remain twenty-four hours in his rear--Escape without

loss--Mississippi lady refugee refuses forage--Compelled to take

it--Back to camp--Cross Chattahooche river, and ordered to intercept

cavalry raid near Newman--General Johnston relieved, and General

Hood in command--Regret, almost despair, in the army--General Dick

Taylor's account of trouble between Mr. Davis and General

Johnston--Brigade ordered to Atlanta, regiment ordered to

battle-ground of 22d of July. . . . . 175 CHAPTER XVIII.

Want of

confidence in General Hood--His opinion of the infantry of his

army--His opinion of his cavalry--Fearful sights on battle-ground of

22d July--Skirmishes in cornfield--Ordered back to left of army,

rejoin Armstrong--Enemy advances on Lick Skillet road--Ordered with

part of regiment to extreme left--Attack on my command--Driven

back--Advance of General Lee's corps--Battle of 28th of July--Severe

loss--Federal raids to our rear--Fight with Killpatrick--Back to

left of army--General Sherman's move to our left--Constant fighting,

fall back to Jonesboro--Occupy trenches, first assault of enemy

repulsed--Loss of Jonesboro and evacuation of Atlanta. . . . . 188

CHAPTER XIX.

Some reflections on loss of Atlanta--President

Davis visits camp--Ordered by General Jackson to take command

disabled horses and men--Ordered to reinforce General Tyler at West

Point--Orders and letter from General Jackson--Ordered to

Mississippi with my command--Incidents of the march--Sick in

hospital and leave of absence--At home again--Met a gold bug on the

road . . . . . 201 Page xiv

CHAPTER XX.

Rejoin army at

Tupelo--Disastrous condition as seen by General Taylor--Brigade

furloughed two weeks--A young recruit to Bolivar troop from New

York, but native of Alabama, Henry Elliot--Reorganization of cavalry

at Columbus--Appointed on examining board--Legislature in

session--Speeches by prominent men--General Forrest--General

Taylor's opinion of him--Military execution--Ordered towards Selma .

. . . . 220

CHAPTER XXI.

Last letter to my wife, very

gloomy--Cross Warrior river, move to Marion--New York recruit sees

his aunt--Thrown in Wilson's front--Night march, fall back on

Selma--Enemy attack Selma--How General Taylor escaped--Description

of battle--Regiment nearly all killed, wounded or captured--Brave

Federal sergeant saves my life--Took my pistol and hat, but didn't

want Confederate money--Sorrowful night--Federal band plays "Dixie,"

insult to injury. . . . . 233

CHAPTER XXII.

Walk over

battle-field under guard--Dead and wounded--Henry Elliott, tribute

to him--Adjutant Johnson mortally wounded--Put in stockade--Kind

treatment by Federal of officers and men--March to Columbus,

Georgia--Lieutenant-Colonel White, of Indiana--Conversation with

him--Colonel Pinson and myself paroled at Columbus--Make our way

back to Mississippi--The war over--Death of Mr. Lincoln, sorrow at

the South--Meridian, Ragsdale House, cost of coffee at meals--Trip

home and incidents--Home again, negroes free--Doubts as to

future--Determined to stand by the state to the end . . . . . 247

CHAPTER XXIII.

Changed condition--President Johnson's plan of

reconstruction--Negroes, old Uncle Hector--Negro problem always

serious--General Alcorn's opinion of right policy--Reconstruction

under act of congress--Negroes voting--Convention, carpet baggers

and scallawags--Our new clerk, Florey--Negroes on juries . . . . .

262 Page xv

CHAPTER XXIV.

Civil government under

carpet-baggers--Visit to Jackson--Legislature of 1870--Governor

Alcorn tempted by seat in senate--Judges, jury trial, and negroes as

jurors--General Starke sheriff of Bolivar--B. K. Bruce--His manners

and conservatism--Campaign of 1873--Alcorn and the

chancellor--Correspondence with Governor Alcorn--Campaign of

1875--Rout of carpet-baggers by tax-payers . . . . . 274

CHAPTER

XXV.

Campaign of 1876--John R. Lynch--Twenty negro laws, his

anecdote--Elected to legislature--Commissioner to Washington City in

1882 and 1884 in interest of levees--Captain Eads--Congressman Jones

from Kentucky--Funeral of Mr. Davis in New Orleans--Elected to

legislature from Coahoma county--Appointed circuit judge--Moral

influence of the bar--Golden wedding tributes--Conclusion--The Star

of Mississippi . . . . . 291

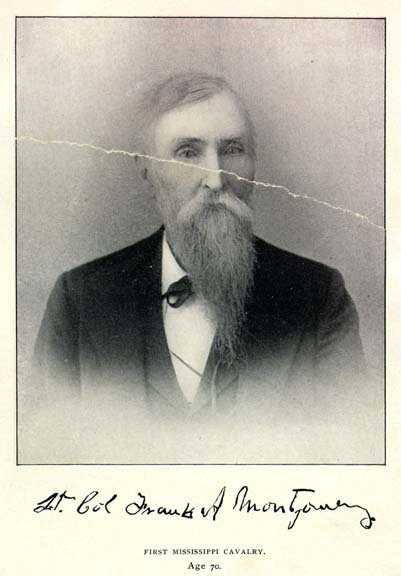

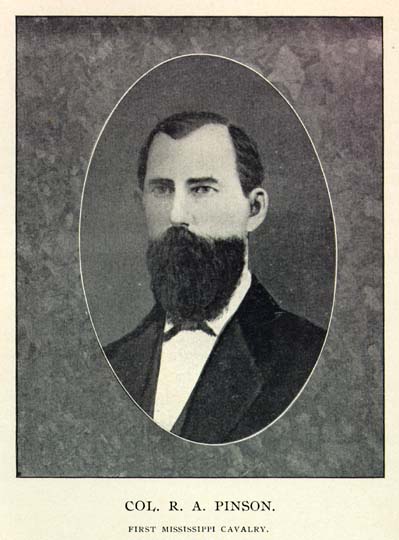

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

Lieut.-Col.

Frank A. Montgomery (age 70), . . . . . Frontispiece Lieut.-Col

Frank A. Montgomery (age 31), facing p. 44 Col. R. A. Pinson, facing

p.75 Frank C. Armstrong, facing p. 157

Page 1

CHAPTER

I.

Introduction--Birth place--Old Natchez trace--Lost villages of

seventy years ago--Territory of Mississippi--Ancestors--Country

school--Oakland College--Its president--His lecture one

day--Political speech of Dr. Duncan, of Ohio--Whig party--Excitement

in Mississippi in 1851--Senators Jefferson Davis and Henry S.

Foote--Speeches by them--Tragic death of Dr. Chamberlain--Fate of

Oakland College.

For some years past I have purposed if

I lived to the age of seventy to write the story of my life. That

time has now come, and I have the leisure for the first time in my

life since I have been grown, for, though active and vigorous still

and capable of work congenial to me, I have nothing to do except to

amuse myself with my pen.

I have lived through the

greatest part of the most eventful century in the world's history,

and while I have filled no great place in the history which I, in

common with all other men living during this time, have helped to

make, yet my story may not prove uninteresting to those who read it,

and it will at least serve while I am writing it to recall the past,

the friends I have known, the pleasures of my youth, the stirring

events of my manhood, till age has now come to warn me that my time

is short, and that what I do I must do quickly.

Though

not a great man in the events I record, yet

Page 2

what I

did and what I saw I can tell, and there are those still living who

will be glad to read what I write; and it may even be that it will

be of some value to some great historian of my state and of the war

who is yet to come. For true history is gathered from small details

by comparatively obscure men who write of their times, as well as by

men who filled larger places in the eye of the world. In writing

this story of my own life I must of necessity have something to say

of the men I have known who filled far more important places than I

did, and who now with few exceptions have "passed over the river."

When I have occasion to speak of them, while I do so freely, I will

I hope do so kindly.

But one great purpose I have in

writing, is to give as far as I can the details of the operations of

the cavalry command to which I was attached during the great war

between the states, for these are never given in the reports of the

great commanders or in the histories which are compiled from them,

except when some great exploit by a Forest, or Wheeler, or Stuart,

is mentioned. The busy and constant service of the cavalry, its

innumerable fights, and constant loss of life, is rarely if ever

mentioned.

It is to supply to some extent this omission

as to my immediate cavalry command, as well as for other reasons,

that I write this story. I am not, I think, either a vain man or a

boastful one, and I regret that I must of necessity use the personal

pronoun "I" many times in what I write, but my purpose is to tell a

continuous story, and I cannot otherwise do it, at least not so

well; so I hope I may be pardoned by my readers. It is not so much

what I did that I want to tell as it is what the brave men with whom

I served did.

It is a source of deep regret to me that I

have not every name and that I will not even be able to give the

Page 3

names of all who died in the various affairs of which I

will tell, for it is these men whose names I would gladly make live

as far as I can. The great men who commanded our armies with few

exceptions deserve the honors they won, but it is the unknown and

forgotten who won their honors for them.

Some of the

great commanders on each side have told their stories, and these are

of more or less value in making up the history of the war, but few,

if any who held subordinate places have recorded their observations

or their experiences as soldiers either of the Federal or

Confederate armies, and this is to be regretted, for there were men

in the ranks who could if they would have told interesting stories,

and even yet there are many who can do it if they will, and I hope

others may yet do it. But whatever is done must be done soon, for a

few more years and there will be none left to tell, for especially

what Mississippi and Mississippians did in that great war, and thus

aid the historian who is to come in writing the history of the war

and of the state.

Our brave foes have been more

fortunate than we have been, for there is probably not a name of any

man who served in their ranks or who died for their cause whose name

has not been preserved, and their dead lie in well-cared-for

cemeteries guarded with jealous care, that future generations may

see how brave men died for the Union and how a grateful people have

honored their memories.

We of the south, whose dead

nearly all lie on the battlefields where they fell, grudge not these

honors to the gallant dead, who while they lived were our foes; we

only ask that history may truly tell our side of that time "when

Greek met Greek." This will be done, though the time may not have

fully come.

But now to my own story.

Page 4

I was born January 7, 1830, in Adams county, Mississippi,

within about a mile of a place called Selsertown, and which, though

there is now no town, still I believe retains the name. The place is

twelve miles from Natchez, and a tavern was kept there for a long

time, perhaps still is, though the railroad which now runs near it

from Jackson to Natchez has nearly destroyed the usefulness of the

celebrated highway upon which it was situated except for local

purposes. This was the road cut in the earliest history of the

territory of Mississippi from Nashville, Tennessee, to Natchez,

along which General Jackson rode when he sought and found his bride

at the home of his friend, Colonel Thomas M. Green, on the banks of

Coles creek, and along which he marched his victorious troops when

returning after the battle of New Orleans. It was then the great

thoroughfare for all travel north from Natchez, and most of that

south to Natchez, for few cared to risk the dangers of river travel

in those days. At intervals of about six miles along this road, in

the early settlement of the territory, little villages had been

located as I remember, between Natchez and Port Gibson, first

Washington, once the capital of the state, then Selsertown,

Uniontown, Greenville, Raccoon Box, and one other, the name of which

I have forgotten, Red Lick, I believe, and then Port Gibson. All of

these villages are gone save only their names, and these forgotten

except by a few old men like myself, and except that Washington

still remains, a small village preserved perhaps by the college

located there. The history of this part of the state always

possessed and still does, a romantic interest for me, because

perhaps, when a boy I knew many of those who had either been among

its earliest settlers, or were their descendants then grown, and who

loved to talk of their trials, of the Indians, of the Spaniards who

owned the

Page 5

country when it first began to be settled

by American pioneers, and of highway robbers who sometimes waylaid

the solitary traveler. Some of the stories I may tell as I recall

them. The story of the ill-fated tribe of the Natchez, of the French

occupation, then of the English, then of the Spanish, and last, its

cession to the United States, all combine to make the history of

this part of Mississippi of absorbing interest, and growing up at

the time and place I did, it is little wonder that it still

possesses a charm for me, and that I love to dwell even now upon it.

From the south boundary line of what is now Claiborne

county, to Natchez, I know every hill and spring and stream, for

twenty-five years of my life, the days of my youth, were spent

midway between Natchez and Port Gibson, and memory often takes me

back to those scenes of my youth. But if I dwell too long on these

things I will never tell my story.

While still an infant

my father moved into Jefferson county, and soon after died. He was

James Jefferson Montgomery, son of Alexander Montgomery, one of the

pioneer settlers of the territory, of whom Claiborne in his history

of Mississippi, makes honorable mention as one of the leading

citizens of the territory and of the state till his death, a few

years after its admission into the Union. My mother was the youngest

daughter of Colonel Cato West, also a pioneer, who became secretary

of the territory under Governor Claiborne, and for some time the

acting governor when Claiborne went to New Orleans as governor of

the newly-acquired territory of Louisiana.

Colonel West

was an intimate acquaintance and friend of General Jackson, and I

have now in my possession a long autograph letter written to him by

General Jackson in the year 1801, devoted to personal matters and

politics, and directed to "Colonel Cato West, Coles Creek,

Mississippi Territory." After my father's death, my

Page 6

mother went to live on our place on Coles creek, about two miles

from Uniontown, which was at the time still a little village, and

not far from the Maryland settlement, so called because some of the

earliest settlers were from Maryland. The old highway spoken of ran

through our place. Here after some years my mother married a Mr.

Malloy, a Presbyterian minister, but she died while still a young

woman, and the plantation and negroes then fell to me. In my early

boyhood, and while she lived, I spent much of my time with my uncle

Charles West, near Fayette, in Jefferson county, and went to school

to a Mr. Roland, a Welshman, who certainly did not spare the rod, or

rather the ferule, which was his favorite instrument of torture.

That was the rule in those days; all teachers whipped their

scholars, and indeed parents all approved it. We live now in a

better day, for the best teachers rarely, if ever, resort to

corporal punishment, which only tends to degrade a child and harden

him.

After a few years with Mr. Roland, who was an

educated man, becoming afterwards an Episcopal minister, I was sent

to Oakland College, when about twelve years old, and remained about

five years and till after the death of my mother. Oakland College

deserves more than a passing notice, both because of the tragedy in

the year 1851, when its venerable president was slain at his own

door in open day by a neighbor, and because of its singular destiny

in after years, at least its undreamed of destiny, by those who

founded and supported it. Oakland College as I first knew it, and

before the war between the states (I have not seen the place since),

had an ideal situation for a college. In the southwestern part of

Claiborne county not far from the line, the nearest town was Rodney,

five miles away in Jefferson county. The cottages in which the

students roomed formed a semi-circle on the crest of the ridge, with

the main college

Page 7

near the center, and close to this

the president's house. In front was a campus covered with oak trees,

and sloping down to the common boarding-house, and at each end of

the semi-circle the halls of the literary societies, the

Belleslettre and the Adelphic. I belonged to the first. The college

was founded mainly by Mr. David Hunt, of Jefferson county, supposed

to be the wealthiest planter of his time, and the Rev. Dr. Jeremiah

Chamberlain, who was its president. Dr. Chamberlain was an eminent

divine of the Presbyterian Church, and was a most lovable character.

Genial and whole-souled, the boys and young men all loved as well as

respected him. He had also quite a vein of humor in his nature, and

this would crop out at unexpected times. I remember once when he was

hearing a class in rhetoric or logic, in his lecture to the class he

repeated the following lines, which I at least have never seen in

print, but which though it is more than fifty years ago I have never

forgotten:

"Could we with ink the

ocean fill,

Were earth of parchment

made,

Were every single stick a quill,

Each man a scribe by trade,

To write the tricks of half the sex

Would drink that ocean dry.

Gallants, beware, look sharp, take care,

The blind eat many a fly."

I

don't remember what else was in that lecture, but that caught me and

has staid. It was well known that the doctor was an ardent Whig of

the Henry Clay and Daniel Webster school, and the boys sometimes

took advantage of it to tease him if they could. I recollect in the

campaign when Mr. Polk was the candidate of the Democrats, I came

across a speech made by a Dr. Duncan, of Ohio, which was a red-hot

Democratic speech, and as my time to declaim before the president

and

Page 8

students was near at hand, I committed some of

the most eloquent parts to memory to speak, counting in advance on

the good doctor's indulgence. I was urged, too, by many boys who

said I was afraid to do it.

It seems that in some parade

of the Whigs in some Northern state they had a banner with this

inscription: "We stoop to conquer." This excited the ire of some

poetical Democrat who wrote a piece with which Dr. Duncan closed his

speech. Two verses I remember yet:

"

'We stoop to conquer!' who are 'We'

That

from our mountain height descending

With

golden bribe and treacherous smile,

With

the sons of freemen blending,

Sow the

seeds of vile corruption?

Poor

nurselings of the Federal 'style,'

Fed

on the husks of aristocracy--

'We' quail

in fear beneath the eye

Of nature's true

and tried Democracy."

The last verse I gave with all my

power, turning to the doctor and pointing at him. When I got

through, he asked me where I had got the speech, and when I had told

him, only said as I had spoken better than usual, he had not stopped

me. In fact, though a boy, I was myself a Whig, and I did not loose

my faith and hope in that most glorious of all political parties

this country has ever seen, till the election which gave us Mr.

Lincoln and bloody war.

Dr. Chamberlain was not only a

Whig, he was an uncompromising unionist, and to something growing

out of this he owed his death.

At the time, the summer

of 1851, during the vacation, I was married and living on my

plantation some twenty miles from the college.

The

compromise measures as they were called, under which I believe

California was admitted to the Union,

Page 9

had excited a

great deal of feeling in the South, higher in Mississippi and South

Carolina than in any other states. The two senators from

Mississippi, the somewhat erratic, but brilliant, Henry S. Foote,

supported the compromise, while Mr. Jefferson Davis had opposed it

in congress. A convention of the people had been called, and feeling

ran high. During the canvass I heard both those distinguished men,

and candor compels me to say I thought Mr. Foote the superior of Mr.

Davis on the stump. I remember one thing Mr. Davis said which was

applauded both by those who supported him and those who did not. It

was thought by many that South Carolina would secede then, and Mr.

Davis said, if that state did secede and the Federal government

attempted to coerce her, he for one would shoulder his musket and go

to her aid. The sentiment was loudly applauded, for none in this

country at that time denied the right of a state to secede and set

up a government of its own if its people desired, with or without

reason.

Among the members of Dr. Chamberlain's church a

wealthy gentleman living near the college, named Batcheldor, was as

ardent a secessionist as the doctor was a union man. It was reported

to this gentleman by a Mr. Briscoe, himself a secessionist, that Dr.

Chamberlain had said that no man could be a secessionist and a

Christian. They had met by accident in the town of Rodney, and with

other gentlemen were discussing the all-absorbing topic of the day,

when Mr. Briscoe made this statement, not as I remember as a fact,

but as something he had heard. Without a thought Mr. Batcheldor said

to him, "You may tell the doctor I am a secessionist."

Mr. Briscoe was a member of a prominent family living near

the college, and had to pass through the

Page 10

college

grounds on his way home. He was seen to stop at Dr. Chamberlain's

gate and get off his horse, and the doctor walked from his porch to

his gate, only a few feet away. No one heard what passed, but the

doctor was seen to open the gate and pass through, and then turn and

walk back to his house and, in the presence of his horrified wife

and daughters, saying "I am killed," fell dead. He had been stabbed

to the heart, a heart whose every impulse in his long and useful

life had been for the good of his fellow-men.

The news

spread like wild fire, the prominence of the doctor and his

blameless life, the prominence of the family of the unfortunate who

in a moment of madness without conceivable motive had slain him, all

combined to excite the people to madness. Hundreds hastened to the

college and dire threats of vengeance were made, but Mr. Briscoe

could not be found. After striking the fatal blow he had mounted his

horse and gone in the direction of his home, and for some five or

six days this was all that was known of him. Then he was found by a

negro in a pasture not far from the house of a relative, a Mr.

Harrison, in a dying condition from poison. He was taken to the

house unconscious and soon died. After the war between the states,

Oakland College was sold to the state and became Alcorn University,

a college for negroes, and is now the Alcorn Agricultural and

Mechanical College, devoted to the education of that race. Who of

its founders or those who supported it, or the proud young men who

filled its halls, could ever have dreamed of a fate so strange, and

to me so sad, for this college, once the pride of South Mississippi!

And yet this change in Oakland College is a small thing compared to

that upheaval and destruction of southern homes and southern society

caused by that bloody war for the preservation of that Union which

Doctor Chamberlain

Page 11

and thousands of others in his

day loved so well, even in Mississippi, which a few years later was

to be one of the first of the states of the South to break or try to

break the bonds which bound it to the Union.

The names

of Dr. Chamberlain and Mr. Hunt have been perpetuated in the name of

the Chamberlain-Hunt Academy at Port Gibson, and long may they live,

though few perhaps know of the tragic fate of Dr. Chamberlain or the

unostentatious life of the ante bellum millionaire, Mr. Hunt.

I remained at Oakland College till I had gone through the

junior class, and then the Mexican war having broke out, though

under age, having no one to restrain me, I left the college to

become a soldier. In this hope I was disappointed, as the result of

my efforts will show.

Page 12

CHAPTER II.

Mexican

war--Jefferson troop--General Thomas Hinds--Natchez fencibles,

Captain Clay--Vicksburg--Mustering officer, General

Duffield--Company rejected--Trip to Jackson--Governor Brown--General

McMackin--Alleghany College, Meadville,

Pennsylvania--Concert--Escaped slave--Copper cents--Skating, sleigh

riding--Militia muster--Home again--Cotton planter of those

days--The negro as he then was--As he is now.

My first

effort to be a soldier was to join a cavalry company, gotten up by

Charles Clark, then a lawyer living in Fayette, Jefferson county.

This was a great man, and in another place, when I shall have

occasion to mention him, I will pay a tribute of love and admiration

to his character and services to his state. Our company was to be

called the Jefferson Troop, after the celebrated company commanded

by General Thomas Hinds in the battle of New Orleans, of whom

General Jackson, speaking of its charge upon the British lilies,

said: "It was the wonder of one army and the admiration of the

other." I knew General Hinds in my boyhood days, and remember him as

a fine old gentleman of the olden time. For him the county of Hinds

was named, and thus his name will live as long as the state does.

After some weeks of drilling, it being found no cavalry was wanted

from Mississippi, we disbanded, and I went to Natchez and joined a

company commanded by a Captain Clay, and called, I believe, the

Natchez Fencibles. Captain Clay took, as he supposed, a full company

to Vicksburg to be mustered into service. Certainly, as I remember,

it was a fine company, but there was politics in those days as well

as

Page 13

now, for it was charged openly it was due to the

desire of the state administration to keep a place open for a

company from some other part of the state, which was always true to

the Democratic party of the time, that Captain Clay's company was

not mustered in, it being from a staunch Whig county. Anyway we got

to Vicksburg and were assigned quarters in the old depot building,

where, after remaining a few days, we were brought out by General

Duffield, to be, as we supposed, mustered into service.

I recollect him well as dressed in a gorgeous uniform, with

a cocked hat and waving plume, a long saber by his side, he strutted

along our line. Since that time I have seen "Captain Jinks, of the

Horse Marines," on the stage, and I at once thought of General

Duffield, and when I think of one now the other comes before me. As

he came to me he stopped and asked how old I was, and when I told

him he ordered me out of the ranks. There was another young fellow

of my age in the ranks whose name was Fauntleroy, and heal so was

ordered out; and having thus reduced the company below the minimum,

he promptly rejected it. We were all indignant, as were many

prominent citizens, and it was decided to go to Jackson and lay our

case before Governor Brown. We succeeded in getting an engine and

some box cars, and got to Jackson late in the afternoon, but the

governor was reported sick and could not be seen. He had not gone on

a distant fishing excursion, as I have known one governor to do, in

order to avoid an unpleasant interview. We did not get to see him,

but we had a high time. Any number of speeches were made, and it was

openly charged that he was keeping a place for a favored company for

political purposes. There was great excitement and danger of

personal difficulties, but happily these were avoided.

Page 14

After a while we were taken to supper at a hotel

kept by General McMackin, whom I then saw for the first time. I took

him to be some intoxicated man as he went around crying out his bill

of fare: "The ham and the lamb and the jelly and jam and blackberry

pie, like mama used to make." The reason he gave for this habit was

that when he first opened a hotel in Jackson, so many members of the

legislature could not read, he had to do it in order to let them

know what his bill of fare was. Long after this when the

carpet-baggers, who had swooped down on the state "like a wolf on

the fold," had got full control, I was at a hotel kept by the

General in Vicksburg, the old Prentiss House, and to my surprise I

found bills of fare on the table. He had just commenced this usual

mode of letting his guests know what there was to eat, but he was

still from the force of habit walking up and down the dining-room

calling his bill. As he passed near me, I called to him and he came

at once, for no host was ever more polite and attentive to his

guests. I said to him: "General, I am sorry to see those bills of

fare on your table." "Why, why?" he said. "Because," I replied, "it

would seem to intimate that you thought the state had become more

intelligent under this carpet-bag rule than it was in the good old

days before the war."

In a voice that could be heard all

over the dining-room, he cried: "I'll burn 'em every one up; I'll

burn 'em every one up!" and I believe he did, for I never saw them

on his table afterwards.

We got back to Vicksburg the

same night (tired out I slept all the way back on a pile of

muskets), without having seen the governor, or got any satisfaction

as to whether our company would be received. We staid in Vicksburg a

few days, and the company gradually broke up, some of the men

joining other companies, and

Page 15

some going home. For

myself, I was disgusted and went home, for I would not join a

company where I did not know either the men or officers.

My guardian advised me to return to college for at least

another year, and this I was willing to do, but I was unwilling to

go back to Oakland College, as I preferred to go north. I did not

care what place so it was in the north. To this he consented, and at

his request I concluded to go to Alleghany College in Meadville,

Pennsylvania. He knew nothing of the college, except a young man

from the north who had taught school for him and who had kept up a

correspondence with him was then a student at it. Meadville was

ninety miles west of Pittsburg, and the trip from my home in those

days was a long and tedious one. I embarked at Rodney on a steamboat

named the Ringgold, after Major Ringgold who had been recently

killed in the battle of Palo Alto or Resaca, I forget which, and

after a long trip got to Louisville, there took another boat to

Cincinnati, and then another to Pittsburg, where I took the stage to

Meadville, arriving at that place after an all day and all night

ride, a little before day. My first care after breakfast was to look

up my guardian's friend, whose name was Mills. I found him at the

college and was at once made at home with him. He was some years

older than I was, but he was a fine fellow, and we became and

remained great friends, though he played me a little trick that

night. Except Mills, there was not a human being in the town I knew,

and he I had only seen that morning for the first time. Meadville

had at the time about twenty-five hundred inhabitants, and had its

very exclusive set in society as I afterwards found out. There was a

concert to be given at the hotel at which I was staying that night.

A young man was to sing, and I proposed to Mills to come and take

supper with me and

Page 16

go with me, and he agreed, but

said he knew some young ladies and proposed we should take them, to

which of course I made no objection.

He introduced me to

his friends, two sisters, who I saw at once were two very

respectable girls, as indeed they were, but I could see were not

much accustomed to society. However, I did not know anything about

the people we were to meet at the concert, so I did not much care.

Neither of the girls was pretty, and both were much

older than I was, but Mills took the youngest and prettiest one and

left me the other. It was a long walk to the hotel and I was very

much bored by my company, but I took care not to show it. I could

see at once from the company assembled that the elite of the town

were there, and that our girls were out of place, and I felt sorry

for them and somewhat ashamed for myself. I don't think Mills had

ever been to an entertainment before, and I never knew him to be

afterwards where ladies were to be present. How it was he ever

became acquainted with these girls I don't know. Their father owned

an apple cider mill and a distillery, as I found later. I did not

desert my charge, but paid her marked attention, till I had got her

safely back home, but after one formal call for politeness, I never

saw her again, though I remained in Meadville a year.

When I became acquainted as I did with most of the young

ladies who had been at the concert, I was often teased about my

first appearance in society. The singer's name was Sloan, and he

sang well, and for the first time I heard Napoleon's grave, a fine

old song.

I was a young man fresh from a southern state

and had never been north before, but I was treated with extreme

kindness, and before I left had many warm friends. There was a great

deal of curiosity about the south and

Page 17

about slaves,

and I was surprised at the ignorance of those whom it seemed to me

ought to have been better informed, but there was little travel

between that section of the country and mine. Indeed, I don't

remember to have seen but two men from the south, and one of those

was a relative of my own who came on and joined me after a few

months, and the other a young student from Maryland, which was

called a southern state because it was a slave state. There were not

very many avowed Abolitionists in town, but they were very bitter.

The general feeling then was that slavery was a matter for the south

to deal with, but if a runaway negro happened to come through the

town, he was helped along by everybody, and sometimes one did come

escaping from Maryland or Virginia. One came while I was there and

advertised to give a lecture. To everybody's surprise, I did not go,

for two reasons: one that I had no desire to see the negro, and the

other because I was pretty sure the wild young fellows would raise a

row, as actually happened. I was told by some who went that he was a

very ignorant negro. There were very few of that race in town, some

barbers and one old fellow who said he was an escaped slave from

Maryland a good many years before, were all that I knew anything

about. The latter soon took a liking to me and waited on my room,

though every now and then he would get a little tipsy and tell me I

couldn't whip him like I could in Mississippi. Sometimes I would

pretend to be angry and start towards him when he run, and once fell

downstairs being a little fuller than usual, and I had to go down

and help him up. I reckon the old fellow liked me chiefly because I

was free with my dimes and quarters, and did not put him off with

copper cents. These copper cents were the old fashioned kind, as big

as a half

Page 18

dollar, and at first when offered me in

change I would not take them; but I soon found that would not do, as

they were a very useful coin in that country and are no doubt to

this day; and it will be a good thing for the south when they come

into general use here. Everything seemed to me to be cheap in that

country; my board with a room to myself, fires, lights and washing

furnished, was only two dollars a week. After the battle of Buena

Vista, where the Mississippi regiment saved the day, Mississippians

were at a premium, and being the only one in town, I shared in the

glory without having been in danger, as I would have been had

Captain Clay's company been received.

At Alleghany

College, in Meadville, I found that the vacation was in the winter

for three months, commencing the first of December, so I was not

there long before the vacation commenced. One reason for this was,

as I was informed, that the young men might teach school in the

country schools at a time when the children could be spared from the

work of the farm to go to school. I was in my room one day when a

farmer came in and introduced himself as the trustee of a school a

few miles away, and desired to engage me to teach it. I have always

regretted I did not take the school. This left me nothing to do but

to frolic, and I soon had friends enough among the young people to

keep me busy at this entertaining, if not profitable, business.

French creek (I believe that is the name) ran through the town, and

when it froze over I got me a pair of skates--I paid two dollars and

a half for them-- and went down to join a crowd and learn this

exhilarating amusement, but after several severe falls I concluded

it would not pay a Mississippi boy to learn, and I gave my skates

away. I got along much better with sleigh riding though my first

ride was disastrous, for the horse ran away with the cutter and

threw my friend, a

Page 19

young man named Fleury, and

myself out and broke the cutter, for which I had to pay.

What with sleigh rides and dances every week, and sometimes

twice a week, besides other amusements, time did not drag slowly,

but soon brought the opening of the college, and I devoted myself to

it till I concluded to quit and go home.

The arsenal for

North-western Pennsylvania was located at Meadville, and while I was

there a muster of the militia was had, and all the students

attended, of course. There were hundreds of country people, and the

natural result followed, a number of fights between the students and

those people, in which no greater damage was done than black eyes or

bloody noses. I carried the signs of the battle for some days

myself.

Next door to my boarding house lived a Dr.

Yates, whose wife was a sister of James Buchanan, then the secretary

of the navy, I believe, and afterwards president of the United

States. The doctor had a very pretty daughter, who married a young

man, a friend of mine, named Dunham, and I was a frequent visitor at

their house, as I had also made the acquaintance of the doctor's

son, a midshipman, who was at home a good deal on leave.

When the civil war broke out I always looked to see if this

young man ever arose to any distinction, but I never saw his name

mentioned; perhaps he died before the war.

I spent a

year in Meadville, but I can't dwell on that time, pleasant as is

the retrospect.

I returned to my home and, with the

consent of my guardian, went at once to live on my plantation, which

was under the care of an overseer. I wished to learn the duties of

my station, and fully made up my mind to spend my life as a cotton

planter. I think looking back

Page 20

to that olden time the

most delightful existence, and the most iudependent a gentleman

could have.

The highest ambition of all men in the south

at that time, so far as occupation was concerned, was to be a

planter, and to spend the most if not all his time on his

plantation. For this, the merchant invested his profits, the lawyer

his earnings, and indeed everybody saved all he could to attain to

this ideal life. The planter living upon his own lands, surrounded

by his slaves, a happy and childlike race in that day, dispensed a

broad and generous hospitality; no one was ever turned from his

door. For even the lowliest a place was found. His neighbors were

everybody within a day's ride from his home, and frequent visits

were made, the planter mounted on his splendid saddle horse, his

favorite mode of travel, and his wife and children in the carriage.

He was a proud man, proud of his wife and children, proud of his

plantation and slaves, proud of his stainless honor, and ready to

exact or give satisfaction for wrongs fancied or real, suffered or

done, not by the deadly pistol concealed in the hip pocket, but by a

meeting upon the field of honor, with mutual friends to see fair

play. These were the halcyon days of the south, gone never to

return, but the stories of those days, the sacred traditions, have

preserved, and will, I hope, continue to preserve the same spirit in

the descendants of those noble men, and keep them pure in race and

upright and honorable. In this lies the hope of the south to-day.

But what pen can do justice to southern society as it was before the

war, its wide influence for good all over the land; mine cannot. I

speak of a class and not of individuals, for there were rare

exceptions who were coarse and rude, as there are to-day men who,

forgetting the traditions of the past, destitute of gratitude and

honor, flaunt themselves in

Page 21

high places, scheming

only how best they may deceive the credulous and achieve their ends.

I have said that the negro of that day was a happy and

child-like creature. He had no wants not willingly supplied; he had

no care; his day's work done, he slept secure. Crime was literally

unknown to him. The planter left his wife and children on his place

surrounded by his slaves; sure that they were safe from harm.

Now, what is his condition? I speak not of a few bright

exceptions. Ask the jails, the penitentiaries, the lunatic asylums,

which are filled not from the ranks of the old slaves, but their

sons and daughters. No white man will now leave his family on his

place, surrounded by negroes alone, and often when I have been on

the bench, I have been constrained to excuse jurors for this reason.

Insanity was as unknown among negroes before the war as

homicides; each was extremely rare. I don't remember in those days

but one really crazy negro, though there were occasionally idiots,

and though we have now two large asylums, the jails are filled with

those who cannot be received. The homicides now committed by negroes

upon each other constitute the most frightful chapter in the history

of crime ever known among any people. This is easy to prove. What is

to be his ultimate destiny, no man can tell, but his only hope at

last is in the white people of the south. I take no account of the

comparatively few negroes in the north, nor do I here speak of the

negro in politics. This will come later.

Page 22

CHAPTER III.

Railroads--Shinplasters--Customs of the

times--Barbecues--Camp meetings--Militia drills--Shooting

matches--Music of the times--The preacher and the

robber--Indians--S. S. Prentiss--Dueling.

Before I

proceed with my story, I must pause to indulge in some reminiscences

of that far away time when I was a boy in Jefferson county, and give

some account of the manners and customs of the people and of their

amusements, and this chapter may be taken by way of parenthesis.

There were in those days no railroads, the first in the state being

the short line from Jackson to Vicksburg, over which I made my

memorable trip to interview Governor Brown. One other was projected

north from Natchez, and was actually finished for some seven or

eight miles, but this fell through for want of funds. It had a bank,

too, I remember, for those were the days of shinplasters as the

paper money of the numerous banks in the state was then called. The

mode of travel for gentlemen was on horseback; for ladies, on

horseback or in carriages.

The first thing when a

gentleman arrived on a visit, if it were not before eleven o'clock,

was to invite him to the sideboard to take a drink. This was the

universal custom except at the homes of preachers or very strict

members of the Methodist Church, and intoxication was rare except at

barbecues or assemblies to hear speeches when politics ran high. The

old fashioned barbecue of that time has passed away, for those we

have now-a-days are unlike them in many particulars.

Page 23

The men did not go to them loaded down with pistols, for

the deadly hip pocket was not then invented, and the pistol of the

day, with its long barrel and ugly flintlock, was too troublesome to

be carried. If arms were carried, and this was rare, it was the

bowie knife or dirk, and no body ever got hurt except the

combatants. Fights were common on those occasions, but they were

almost always fisticuffs, a word and a blow. There was always a

dance on the ground, and at night an adjournment to the nearest

house, when daylight put an end to it the next morning. The music

was the fiddle, played usually by a negro and such music! old men

forgot their age to join in the dance, for it was almost impossible

to hear it and keep still. It makes me young again to think of it;

not the long-drawn-out music of these days, but such soul-stirring,

heel-rocking tunes as "Arkansaw Traveler," "Mississippi Sawyer,"

"Sugar in the Gourd," "Jennie, put the Kittle on," "Nigger in the

Woodpile," "Natchez under the Hill," and others too numerous to

mention. Almost every plantation had its negro fiddler as well as

negro preacher, usually the biggest scamp on the place, and the

happy darkeys would dance to the one and shout to the other some

times the livelong night. The planter and his family often went to

look on.

Those were the days also of militia drills and

of shooting matches, usually following the drill. Everybody between

eighteen and forty-five was required to attend and bring his gun and

such a motley crowd and such an assortment of arms can never be seen

again.

But those were happy days, for if the daily paper

could not be had the good people never felt its loss, for they knew

nothing of it. In these days we can't live without it, for we must

hear the news from all the world every day, and twice a day if we

live where we can get an evening paper.

Page 24

The shooting matches were trials of skill with the long

rifle, sometimes at the head of a turkey and sometimes at a small

mark for beef, and there were many who could rival the skill of the

Leather-stocking.

Camp meetings were another feature of

those days, which have passed away before the advancing civilization

of the times; for if one is held now, I am told, a restaurant is

attached where meals are sold. In the days I speak of a shady grove

was selected near a good spring, and the well-to-do members of the

church--Methodist--for camp meetings, as far as I know, was a

distinct feature of that church, though preachers of other

denominations often helped--would build rude but comfortable

shanties, each large enough to accommodate from twenty to sometimes

forty guests, and to this the owner would move his whole family and

his house servants and keep open house with old fashioned

hospitality.

And then the preaching. With power and zeal

sinners were warned to repentance, and a vivid imagination could

almost see the fiery billows as they enveloped the hopeless, doomed

ones who cried too late for mercy where mercy never came. One sermon

I remember by the Rev. B. M. Drake, the father of a prominent lawyer

now living in Port Gibson. A man of stately presence, his text was:

"Hear, oh heavens, give ear, oh earth, for the Lord hath spoken: I

have nourished and brought up children, and they have rebelled

against me; the ox knoweth his owner and the ass his master's crib,

but Israel doth not know, my people doth not consider." Conceive the

effect which a sermon from this sublime text from the prophecies of

the royal prophet would have upon a congregation already wrought up

to the highest pitch of religious fervor by prayers and hymns, when

the preacher was eloquent and full of zeal for the salvation of the

souls of those who

Page 25

heard him, and which he firmly

believed would be lost forever if they did not repent.

The pioneer Methodist preachers in that territory were an

interesting class. Some I recall--the Rev. John G. Jones, whose

adventures when he was a young man were thrilling to hear; and

another, the Rev. Mr. Cotton, who, when I was a boy, was often at

our house; and I heard him tell of his adventure with a robber, a

story which Mr. Shields, in his Life of Prentiss, tells, I believe,

but a little differently from the way I had it from Mr. Cotton. He

was riding along a lonely road, when suddenly a man with a gun

stepped from behind a tree, and ordered him to halt. He then made

him ride into the woods, and demanded his money. He was like the

apostle, for "silver and gold" he had none. The robber, enraged,

told him to dismount, as he intended to kill him. Mr. Cotton asked

leave to pray before being put to death, and it was granted him. He

kneeled down by the side of a log, and, with closed eyes, prayed

fervently for his own reception into heaven, for the salvation of

the world, and, above all, for the pardon and salvation of the

sinful man who was about to imbrue his hands in his blood. When, at

last, he had finished, he arose, and, lo! the robber had gone. But,

I might fill pages with stories of that time without ever finishing

my own.

These were the days, also, of quilting bees, and

each house had its frame; the wealthiest as well as the poorest

planter's wife would save her scraps and sew them into squares,

stars and diamonds, until enough were gotten to make a quilt, and

then the neighboring ladies would come and gather round the frame

while the busy needles flew, and the busy tongues kept time till the

work was done. This was a source of great pleasure and amusement to

the married ladies, nor were the negro seamstresses, of which there

were always one or more on each

Page 26

plantation,

permitted to aid in this work. Now and then, in these days, one of

these old patch-work quilts may be found, a relic of other days, but

then piles of them were in every house. Sewing machines were not

even dreamed of; indeed, long after this, when my wife began to talk

of getting a machine, I laughed at the idea, for I did not believe

one could be made which would work. In those days, too, cooking

stoves were unknown in the south; it was not until I had been

married seven or eight years that I would consent to buy one. The

kitchen was never in the house, always at a distance from it, and

the fireplace, a huge affair, with an iron crane to hang the pots

over the fire in which boiling was done, while upon a great wide

hearth the coals would be raked out, upon which the skillets were

put to do the baking, while heaps of coal were put on their lids.

These were the days of hoe cakes, ash cakes and Johnnie cakes, and

no such cooking has ever been done since, and it makes my mouth

water now to think of it. But, good-bye to those good old times,

though memory still often brings them back.

In my

earliest recollection, there were a good many Indians still to be

seen in the country; these belonged to the Choctaws, for the brave

but ill-fated Natchez had disappeared from the face of the earth.

They made their last stand on a place known, perhaps, yet as Cicily

Island in what is now Louisiana, not far from Natchez, and the few

who were not killed or captured were dispersed and lost forever as a

tribe. It has been said that the dead Indian is the only good

Indian, and it may be so. But their story is a melancholy one, and

it is a pity a better fate was not reserved for them. They had the

vices of the barbarian, but they had virtues which none of the other

barbarous races ever had. The Indians I knew were a peaceful people,

the women making baskets from cane and the men subsisting by hunting

and making

Page 27

and selling to the white boys blow-guns,

a favorite weapon with the boys to shoot birds with in those times.

While I was still a small boy, the great Prentiss was

often in the county, sometimes attending the courts and sometimes

speaking at the political barbecues.

I remember to have

heard him in two of his great speeches, noticed specially by his

biographer, Shields. One was near Natchez and the other was at

Rodney. I was too young to appreciate his arguments, but I remember

well the words seemed to flow from his lips in a torrent and with

what enthusiasm they were received by his audience, and his face and

figure still dwell in my memory. He was a wonderful man, an

unrivaled orator.

Coming from the land "of steady

habits" to Mississippi, he became in a little while a typical

Mississippian of the olden time, when that name implied all that was

honorable and true. After I grew up and became acquainted with the

life and writings of Byron, I always associated the two together,

for each had the same lameness, and to this physical likeness there

were many things in their temperaments which were alike. Each died

in his prime. The name of Prentiss occurred to me here as I

remembered another custom of that time among gentlemen, an

"imperious custom," as it was called by a noted divine in his

eloquent funeral sermon at the burial of Alexander Hamilton, who had

fallen in his duel with Aaron Burr--the custom of dueling.

Mr. Prentiss fought two duels with Henry S. Foote, but it is

no part of my plan to give an account of these duels, but only to

mention the fact that in those days no man who had any regard for

his honor or character could refuse to fight if insulted or if he

had insulted another. The custom is just as "imperious" now as it

was then, for while the laws condemn it, yet public sentiment will

Page 28

condemn any man in public life, or whose business or

profession makes him prominent, who dares to refuse, to demand, or

give satisfaction on the field of honor in those cases where custom

has made it proper, if not imperative. But I must leave those old

times and hasten on.

Page 29

CHAPTER IV.

Marriage--Move to Bolivar county--Old town of Napoleon--The

hunter--Money--State banks--Overflows and levees-- Battle of

Armageddon--John Brown's raid--Effect in the south-- Election of Mr.

Lincoln.

On the 12th day of January, 1848 when I was but

little past eighteen and my wife not quite that age, I was married

to Miss Charlotte Clark, or, as she was always affectionately

called, Lottie Clark. She was the daughter of James Clark, who had

when she was an infant moved from Lebanon, Ohio, where she was born,

and a sister of General Charles Clark. We had been sweethearts as

long as I could remember, and she also had just returned from school

at Georgetown in the District of Columbia, having while there made

her home with an uncle living in Washington City. The family were

Marylanders, having originally come over with or as a part of Lord

Baltimore's colony, and her father had been born in Maryland, moving

when a young man into Ohio, where he lived till he was induced by

his son Charles, who had preceded him some years, to move his whole

family to Mississippi, becoming a cotton planter. He was not a large

planter, but he prided himself on the knowledge he had acquired of

the business, and especially on the cultivation of his crop, which

was always clean. He took special care in the neatness with which

his cotton was handled in preparing it for market, and it always

brought the highest market price. After I was married I was riding

one day with him through his field and to my surprise he said it had

Page 30

always seemed singular to him that there were red

and white blooms on the same stalk. I explained it to him; but the

fact was he had always been puzzled over it, but would not inquire.

Peace to his ashes; he was a good man and lived to a good old age.

We were young to marry, I especially, but I had for some

years been my own master; no objection was made by any one, I had a

home prepared to go to and ample support assured, and I took my

bride to our home. Our house was large and old fashioned, but

comfortable, and it was our delight to fill it with young people and

have the fiddler from the quarter, as the place where the negroes

lived was called, almost every night, though on set occasions we

would have the music from the towns, Fayette, Rodney, and sometimes

Natchez. In those days we knew no care, but were as light hearted as

our negroes who loved to crowd around the doors and windows of the

great house, as they called the residence in which their owner

lived, to see the fun. I usually kept an overseer, as most planters

did, and had ample time for amusements and reading, of which I was

always fond. I read everything, novels, history and that wonderful

book the Bible, of which I have been a student all my life. I read

also the usual text-books on law, though at the time I little

thought I would ever put this to any use. I had a good library for

the time, of books now out of print, if not also entirely useless,

at least many of them, in these days. My wife always had her hands

full, for what with company, the care of her household affairs, and

the looking after a half dozen servants and more on extraordinary

occasions, about which there was often a dispute if the crop was in

the grass, to which was soon added the care of a family, her time

was fully occupied. And so we passed the days happy when we lived in

Jefferson county.

Page 31

We lived on our

plantation in that county for seven years, when I sold the lands I

owned in that county and in Hinds and moved to Bolivar county to a

plantation I had bought and partly improved a year before. I had

been largely influenced to this move by my brother-in-law and friend

General Clark, who, having given up the practice of law in Jefferson

county, had already moved his family to a plantation he owned on the

banks of the river, not far above the old town of Napoleon, a live

town in those days, too much so for quiet people. It was the port at

which almost all the boats which plied their trade on the White and

Arkansas rivers made and received transhipments of freight, and

there was always a large and tough floating population. I remember a

curious adventure I had on one occasion. I had gone there to get a

boat to go down the river, as boats always landed there, while it

was not always easy to get one to land at other places. I had to

wait all day as it happened, and in one of my walks from the tavern

to the wharfboat, where I could see a long way up the river, I met a

man I had previously seen come into town with a cart loaded with

venison. There was no one near, it being some distance either to the

town or to the wharfboat. This man was in his shirt sleeves and

bloody from his occupation and was talking to himself. He was a

tough-looking customer and I proposed to give him a wide berth, but

seeing me he came directly to me. He had in his hand a five dollar

bill and he asked me to tell him whether it was, good money or not.

He said he had just sold a venison to a steamboat which was at the

landing and got it in payment. It was a bill of some bank in one of

the northwestern states (for every state had its own banking

system), and as I had never heard of the bank I told him I did not

know.

All along the river the country was flooded so to

speak

Page 32

with bills from Ohio, Illinois, Indiana,

Kentucky, Tennessee, and states too numerous to mention. No man

could tell not only whether the bills were genuine or not, but

whether they were worth a copper if they were genuine. Mississippi

alone had no banks of issue, the days of the shinplasters had cured

that state. Some of the banks of Memphis, Tennessee, were supposed

to be good and the bills were taken freely. The banks of New Orleans

were always solvent up to the war, and was the only paper money

which every body in this country would take without question.

I politely excused myself to the man and desired to pass on,

but he would not let me go till I had heard him through, which was

his life from the time he was a little boy when his father married a

second time, when he quarreled with his stepmother and ran away, to

that time. He told me of his success as a hunter, how much he made

and was in the highest degree confidential, that he intended soon to

quit his business and go back to his old home in Tennessee, join the

church and be always a good man. I did not know whether the man was

crazy or drunk, but in either case thought it best to humor him. At

last he admitted my excuses and permitted me to go, but he had

evidently taken a strong fancy to me for he wanted to know if I

wanted any money. I told him no, but he insisted, and pulling out an

old buckskin purse full of gold, evidently several hundred dollars,

told me to take what I wanted. The strange thing about it was, that

in a town like Napoleon then was, a man seemingly so free with his

money should have had any at all. I got away from him and though I

noticed him afterwards on the street I kept out of his way. Not a

vestige remains now of the old town of Napoleon, the insatiable

river has long since swept it away. The county of Bolivar when I

came to it, in January 1855, was an unknown wilderness

Page 33

save a few plantations on lake Bolivar and Egypt ridge, so

called because in the high water of 1844 it was not overflowed, and

a great deal of corn was made on it, and save also a few plantations

along the bank of the river. These plantations were all partly

protected by small private levees, for the entire country was

annually inundated by floods which came down the river every spring,

thus showing the absurdity of the idea some have that the great

overflows we sometimes have are due to the levees. The truth is,

this magnificent country is worthless without protection from

levees, and while we have not yet perhaps complete protection, yet

it is now settled that before many years have passed the great

government of the United States will assume control of the work and

protect the country. Already we have received and do receive great

aid through the river commission, and it is certain that this is

largely due to the persistent and untiring energy, zeal and tact of

one man, the Hon. Thomas C. Catchings, for so many years the member

of congress from the district where the levees are situated.

When General Catchings first became a candidate for congress

the vote of the district was largely, in fact, a majority, a negro

vote, for we had then no franchise law as now, which to a great

extent curbs and curtails the ignorant vote. I recollect in the

first speech he made in Rosedale in his first canvass, and when his

audience was mostly composed of negroes, in speaking of what he

hoped to do for the levees, his opponent being a negro, he told them

that much of the success which a member of congress could hope to

achieve would be due to his social standing with other members; and

this is true, for no matter how able a member might be, his social

qualities, his ability to make friends, his tact, were sure to

accomplish more than all the speeches he would make, no

Page 34