From the WPA Slave

Narratives:

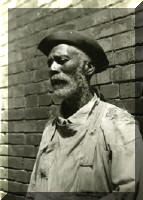

Charlie Bell

Click on photo for larger image - Photo by James Butters

Click on photo for larger image - Photo by James Butters

Charlie Bell, colored, was born at Poplarville, Pearl River County,

Mississippi, in 1856 on the plantation of a Mr. Moore. Charlie does not recall

his master's given name nor initials as he himself was only nine years old

when he was transferred to another owner. But he remembers that Mr. Moore had

four hundred slaves and upwards of six hundred acres in cultivation and that

there were four sons and three daughters in the Moore family.

Just at the close of the Civil War, one of Mr. Moore's daughters was married

to "the Mr. Long-Bell-Lumber Company Bell" and Charlie was one of the nine

darkies, including his own parents, "who just stayed on," as a part of Little

Miss's "setting-out." Hence his surname became Bell by which he is still

known.

Bell, at his present age of eighty-one, is hale and erect, in color medium

brown (as browns in this sense go) set off by a growth of closely kinked

benevolent-looking white wool covering his head, cheeks, chin and most of his

neck. He is five feet, six inches, tall and weighs one hundred sixty-five

pounds. His upper teeth present a solid gold front which condition, be it

noted, is less disfiguring to the negro face than to the white; in fact, the

color scheme is rather good, which may account for the pride most negroes take

in the possession of gold teeth.

Bell's story offers the rather unique item that at the age of eighty-one, he

is still earning his living by his own labor, being now employed as handiman

at the McQuillan Distributing Agency for Fehr's Beer, No. 245, 24th Ave.,

Meridian, Miss. It is not to be assumed, however, that Bell sympathized with

the consumption of alcoholic beverages. On the contrary, he has a very poor

opinion of the practice, rising from the observation of a long life, declaring

"can't no man beat John Barleycorn because he whups ever man that jumps on

him." The suggestion was made to Bell that probably he had never been ill

since he looked so strong and healthy. To this he replied modestly that he

hadn't "been sick any too much;" "aint took a dose of Epsom Salts since 1914."

Interest was felt in how and why Bell left Pearl River County to take up his

abode in Meridian. He supplied this information politely but appeared slightly

embarrassed by the questioner's ignorance. "Taint no piece over there;

I can walk there in a day. I just come to Meridian. Of course when I was a

little feller, our largest city was Mobile or maybe Biloxi." The inference is

obvious, we believe?

On the subject of his domestic affairs, Bell was inclined to be reticent. "Me

and my wife is separated. I just lives with a family in Royal Alley" (this is

near St. Luke's Street on South Side, Meridian, a section more or less given

over to the daughters of joy, regardless of color). "Yes'm, I has chullen but

they aint no good." When pressed to give the number of his offspring: "About

fourteen head of 'em." It was then suggested that he must have many

grandchildren and he agreed that he probably had "a right smart of 'em" but

did not know how many as all his children were grown and living in other parts

of the country.

"I b'longed to Mr. Mo' frum Poplarville in Pearl River County. They was 'bout

fo' hund'ed slaves an' up'ards of six hund'ed acres in cultivation; hit aint

no tellin' how many acres they was in all. I disremembers his fus' name 'cause

I wasn't but nine year old when de Surrender come in sixty-five an' Mr. Mo's

oldest girl mar'ied, an' me an' my mama an' my daddy an' six others was part

of her settin'-out. So we jes stayed on. She mar'ied Mr. Long-Bell-Lumber

Company Bell, an' that's how come my name is Bell 'stead of Mo'.

"My mother was bornd between Poplarville an' Picayune an' my father was bornd

at Red Church forty mile below New Orleans. I have heard say my gran'father

was bornd there too.

My father was a carpenter an' a blacksmith, could make a whole wagon, go out

an' cut him a gum tree an' make a whole wooden wagon, an' hubs an' ever'thing.

That's how come they didn' take him to de War; leave him at home ter make mule

shoes an' things. He was a powerful worker.

"I 'tended de cows an' calves - give 'em water - an' fed de chickens what roos'

in de big hen-house. But 'fo I got big enough ter do that, I stay in de 'long

house' with de other little fellers. It was jes hewed out er logs. They was

notched ter fit - like this - an' dobbed with mud an' pine straw - wouldn't

never wash out. Three of de old women 'tended ter de chullun an' cooked they

sompin'-t'eat. They'd po' syrup in ever'one of 'em's plate an' ever'one of 'em

had a tin cup ter theyse'f fer they milk. They had a big oven like a

frog-stool house, made out er mud. In de summer they moved hit out in de yard

'cause de chullun didn' stay in de 'long house' 'cep' in de winter. Hit was

plum full then, though, an' Miss Mo' she come out ever' day an' teached us

out'n a Blue Back Speller.

"Mr. Mo' built a log church for his labor on de plantation. A white preacher

come twice a month ter speak ter us. His tex' would always be 'Obey yo'

marster an'

mistress that yo' days may be lingerin' upon God's green earth what he give

you. We didn' have no nigger preachin' ter us when I was little.

"Some of de colored folks was pretty sociable. Some of 'em was pretty good

scholards, could read well enough ter go anywhere an' enjoy theyse'fs. De

niggers on de plantation danced a heap - seemed ter me like hit was mos' ever'

night. You takes a coon skin an' make a drum out of hit, stretch hit over a

keg - a sawed-off one - dat make a fine drum. An' banjos an' fiddlers! Didn'

have no mandolines an' gui-tars then.

"I've heard say they didn' never buy medicine. Whenever one of 'em got sick,

they give 'em peach-tree leaves fer chils an' fever an' biliousness; hit was

boiled an' steeped. An' they give 'em red-oak bark fer dysentery; put hit in a

glass an' po' cold water over hit an' drink off er hit all day. Fer jes plain

sprains, they'd make a poultice out er okra leaves; hit ud show draw you! You

know what they'd put on a bad sprain? Put a dirt-dobber's nest an' vinegar.

When de chullun had dem bad colds like they has now, they give 'em hic'ry bark

tea, drink hit kinder warm, drink hit night an' mornin'. Hit kep' dat cough

frum botherin' 'em.

"Mr. Mo' went ter de War an' come back all right. Found things on de

plantation jes like he lef' 'em. You see, when you has servants arouns yo'

house, they keeps hit whether yo' presence er yo' absence is there. I show you

what I means, madam. After Mr. Mo' come back frum de Civil War, he had all de

barns overhauled an' banked ever-thing, turnips an' ever'thing, so he'd be

able ter take care er all his labor he had on de place. Didn't but a few

niggers leave. They all stayed wid him till he died. After he died, they

scattered.

"When de Yankees come down endurin' of de time of de War, I remembers 'em

comin' by an' givin' us candy. They mus' er been a hundred small chullun of us

there. I say ter de old colored woman what looked after us, I say 'Look here,

they aint got no wagons like we got.' They wagons wasn't made like ours. The

Yankees didn' trouble nothin' on de plantation. After I got grown, I found out

why they didn' bother us: 'cause Mrs. Mo' was a Eastern Star sister an' de

Gen'l wouldn' let 'em bother us. I tell you in a minute what his name was. He

was a small-like stout man, had a little beard jes like dis er-way ... I'd

know him right now if I was ter see him. Name Sherman - that was hit.

"I fus' come ter Mer-ree-dian when I was a grown boy. Hit aint no piece over

ter Poplarville frum here. I could walk hit in a day. Of co' 'se, when I was a

little feller, our larges' city was Mobile or maybe B'loxi, but hit's diffrunt

now. Hit took eight days ter go ter Mobile in er ox wagon th'ough de country.

Hit was de cotton market. We'd bring back coffee an' cloth an' shoes an'

things.

"Miss Bell went ter Arkansas ter live after she mar'ied an' tuck us nine

niggers with her. Mr. Bell raised me frum then on right frum his table. They'd

go north ter spen' de summer, er to California sometimes, an' I go with 'em

wheresoever they go. I shined his shoes an' put his clothes in de pressin'

club ever'day. I was with him thirty some years befo' he died. I had three

thousan' dollars worth er stock in de Long-Bell Lumber Company. After while de

lumber bus'ness got mighty bad an' ever'body los' they money, white folks an'

niggers too. I got these here gold teeth after I come ter Mer-ree-dian. Hit's

been my head-quarters off an' on like you know you has headquarters in a big

place.

"I'se worked fer my bread an' meat all my life. I works now fer Mr. McQuillan

Beer 'Stributin' Company. But John Barleycorn, he's a bad feller. Can't no man

beat John Barleycorn 'cause he whups ever' man that jumps on him. Heap er

folks is sick fer that an' if hit aint that, hit's sompon' else. I aint been

sick any too much - aint took a dose er Epsom Salts since 1914.

"Me an' my wife is sep-er-rated. She spent all de money I had an' when de

lumber bus'ness got bad an' I couldn't get no mo', she tol' me I wasn't any

good. So I jes walk off an' lef' her. I jes lives with a fam'ly in Royal

Alley. I has chullun - 'bout fo'teen head of 'em - but they aint no good. They

all grown an' livin' away frum here. I 'spec' I got a right smart er

gran'chullun."

(The information herein was from Charlie Bell himself on July 5, 1937, at

Meridian, and verified at some points by Mr. Casper Phillips, Attorney,

Meridian, Mr. Phillips having known Bell for some years.

Interviewer: Unknown

Transcribed by: Ann Allen Geoghegan

Mississippi Narratives

Prepared by

The Federal Writer’s Project of

The Works Progress Administration

For the State of Mississippi