Summer Trees

The South Reporter, November 7, 1991

by Lois Swanee, Museum Curator

This authentic Greek revival home was built by Sanders Washington Taylor, a North Carolinian by birth, between 1820 and 1850 on hundreds of acres of land he had acquired from the Chickasaw Indians.

In 1826 Mr. Taylor's daughter, Tranquilla, married Spencer Harvey. Harvey's best friend, Robert McCraven, fell deeply in love with Spencer's bride. To save further heartbreak, McCraven moved to another country, now called Texas.

Tranquilla's father, Sanders Taylor, was said to have been a stern taskmaster in dealing with his slaves. One night in April, 1829, a disgruntled slave aiming at old Mr. Taylor accidentally shot and killed Tranquilla's husband, Spencer.

Upon hearing of his friend's death, Robert McCraven returned to Mississippi. Two years later, he and Tranquilla married and during the ensuing years had nine children of their own.

Luckily, Summer Trees escaped destruction during the ravages of the Civil War, Nathan Bedford Forest used the plantation as a camp for his troops while defending Holly Springs. In appreciation to the family, Forest gave his silver curry comb to Tranquilla.

Along with the poetry of Lord Byron, romantically inspired by Greek revival architecture gained great popularity throughout America during the first half of the nineteenth century. The Greek influence in domestic architecture suited both the mild climate and the gracious way of life in southern America.

It is the home of Mr. and Mrs. Alfred Cowles. They purchased Summer Trees in 1969. During this time they have extensively restored the original part of the house and they have added a library, new kitchen, butler's pantry, master bedroom, pool and gazebo.

Summer Trees History, A Story of Families

The South Reporter, December 27, 1979

by Hubert H. McAlexander, Jr.

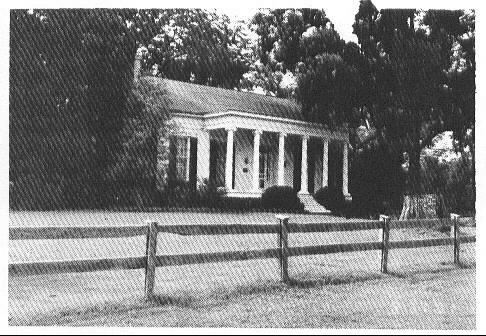

Of the old structures scattered over the hills of Marshall County, perhaps none has been more fortunate than the lovely plantation house known for the last forty years at least as Summer Trees. The mellow beauty of the old brick, the six graceful Ionic columns, and the elegant Greek Revival facade has stirred various people over the years to come forward whenever the place has been threatened by neglect or changing economic conditions. For this treasured landmark (located four miles northeast of Red Banks on Sections 31 and 32, T2, R3), however, we have had no reliable history, only legends – and those have become attached to it only after the Neely Grants saved and carefully restored it in the mid-1930s. These garbled tales have obscured the true story of both the house and the family that built it. The time has come to set the record straight, to give back to the old landmark its real history.

All treatment of the house has begun with the statement that it was built by Sanders Taylor either in 1812 or 1820-25. Any student of the county's past knows, of course, that no building of any pretension was erected here until after the United States government sold the land to settlers in 1836; any student of architecture knows that the high Greek Revival mode of Summer Trees belongs to the 1850s. It is interesting from a search of the land records to find that the land on which the house stands did not even come into the Taylor family until 1851 and that the buyer was not Sanders Taylor at all. These errors in assigning date and builder to the place, however, have provided a false base on which a number of other legends have been built. Space does not permit me to repeat. Let me, instead, simply present the story of the family and the house and in that way correct the many errors now in print.

Though he never owned Summer Trees, Sanders Taylor was an important early citizen of the county, as were his children. Let us first get their history straight before going to the house itself. Sanders Taylor was born in 1783 in Johnston County, North Carolina, the son of the Reverend William Taylor, Jr., and Sarah Sanders. He married Sarah Green in 1805, and they lived in Anson County before moving to Perry County in south Mississippi between 1815 and 1817. Sanders Taylor established himself there as a prosperous planter, but he was to migrate twice more before his death. When he first purchased land in Marshall County in 1837, the deed (Book B, 299) describes him as a resident of Holmes County, where he had evidently settled just a few years before.

Taylor's first purchase in our county was Section 31, T3, R2, located a mile north of the Courthouse square, the approximate center being the present Danger Curve on Highway 78. In these early years he also bought and sold a number of town lots in Holly Springs, where he lived and where he served as town selectman (alderman) in the years 1841 and 1845. In 1841, he was also a member of the Holly Springs and State Line Railroad Company, which unsuccessfully sought to raise funds for a nineteen mile line to connect with the Memphis and LaGrange Railroad. By 1850, he moved to a plantation northwest of the town. Soon afterward, he began deeding most of his property to his youngest and favored child Washington Sanders Taylor. The father probably moved to the place north of Red Banks now known as the Summer Trees plantation after his youngest son purchased it in late 1851. Sanders Taylor died in 1857 at the age of seventy-three. His graved marked by the most impressive monument in the Red Banks cemetery.

Of the ten children born to Sanders Taylor, evidently only five lived to maturity. Two of the daughters, Ophelia A. Taylor (born 1829) and Mrs. Candace Taylor Nicholson (born 1809) appear to have left little mark in this county. The three other children, however, had long connections.

The oldest son, Greenfield F. Taylor (born 1813), came here with his father, settled a plantation north of Chulahoma, and reared four children. Greenfield's oldest son, James S. Taylor (born 1848), married Mattie Bowen of Chulahoma in 1869. At Mrs. Mattie Bowen Taylor's death in 1932, she left one son, Guy P. Taylor of Orion, who died a few years ago and was survived by his widow, who has recently moved to the home of relatives in DeSoto County.

Sanders Taylor's oldest daughter was Tranquilla Taylor (1806-1879), who married Spencer Harvey in 1826. Harvey was murdered by a slave in 1829, either in Perry County or in Covington County, where his widow was living when the 1830 census was taken. This murder has often erroneously been placed at Summer Trees, rather than in south Mississippi. In 1832, the widow married her late husband's best friend, Robert McRaven; and in 1837, the McRavens joined the Taylor party that came to Marshall County. They settled a plantation near the village of Tallaloosa, and, according to one of their descendants, they lived in a large log house on the plantation. Robert McRaven died in 1857 and is buried alongside his father-in-law Sanders Taylor at Red Banks. Tranquilla had two Harvey children and nine McRaven offspring. These married among the Armisteads, Richmonds, Brunsons, and Rossels – all families from the Tallaloosa-Red Banks-Victoria area. The best known of her children in this county was probably Dr. John Sanders McRaven, who practiced medicine in Byhalia. To my knowledge, no descendant is left here today.

The youngest son of Sanders Taylor (according to the family Bible, Sanders had no middle name) was Washington Sanders Taylor (1824-1884), known locally as Wash Taylor. With this man, we now come directly to Summer Trees and its history. Remarkably, Wash Taylor the builder, has been ignored in nearly all previous treatment of the place. By 1851, when he was twenty-seven, Wash Taylor was referred to by John McCartney Anderson in his diary as one of the “crack farmers” of the county. Taylor was, of course, the primary heir of a wealthy man, but he had also done exceptionally well with what he had been given. On 18 September 1851, he purchased from John H. Clopton the plantation north of Red Banks on Sections 31 and 32, T2, R3 – the land on which now stands the house known as Summer Trees. The place had previously been owned by two other prominent citizens of the county – John B. Rogers, a wealthy planter, and the aforementioned Clopton, who, in addition to planting, also owned a mill on Coldwater. When purchased by Wash Taylor, the place already contained a dwelling, a log cabin probably built by Rogers in the 1830s and still standing today east of the brick plantation house. It is particularly instructive to see in such close proximity the log cabin built in our county's earliest days of settlement and the Greek Revival plantation house that replaced it. The two structures give striking physical testimony to the flush times here in the short twenty-five years between the settlement and the Civil War. As far as I know, the survival of two such structures on the same property in our county is unique to Summer Trees.

Summer Trees itself was built by Wash Taylor to house his bride, Ann Elizabeth Park, the belle of Memphis, whom he married in the early 1850s. Miss Park's father was mayor of the city, and one source notes that Park Avenue there was named for the family. Other Parks married into the Poston and Deadrick families. Summer Trees was the home not only of the young couple, but probably Sanders Taylor before his death in 1857, and clearly of his widow, who is listed there in the 1860 census.

Summer Trees, however, housed the Taylors for only a few years; for in 1861, Wash Taylor left Marshall County and settled on a plantation that he had purchased three miles from Memphis, where he entered the cotton commission business as senior member of the firm Taylor, Radford & Company. In 1878, he lost his wife and two eldest sons in the yellow fever epidemic. The year before, he had found it necessary to mortgage his Marshall County holdings. Two years after his death in 1884, this land was sold to settle debts of his estate.

Though the selling of the plantation ended the family's connection with the county, a number of Wash Taylor's descendants still live nearby. Of his ten children, two daughters remained in Memphis: Helen, who married a Mr. Kennedy, and Sallie who married Andrew Jackson Donelson, member of another prominent Memphis connection. Two of Wash Taylor's sons were also long established there, Frank Washington Taylor (born 1859 at Summer Trees) married Florence Goyer and was the founder of both Herron, Taylor & Company, a wholesale grocery house, and F.W. Taylor & Company, a brokerage firm. Joseph Hamilton Taylor (born 1862 near Memphis) married Minnie Cole, whose father founded Cole Manufacturing Company, of which Mr. Taylor served as vice-president. Harry D. Taylor, a third son, was a planter in Panola County in 1923.

After 1861, however the story of Summer Trees is the story of other families. The Taylors owned the place for twenty-five years longer, but after the war they rented it. Their most notable tenant were the Rand family, who with their kin Oscar and Jackson Johnson later founded the International Shoe Company in St. Louis. The next owner after Wash Taylor was William Houston Cannon, who held the property for over thirty years. A number of older residents know the property as the “Hous Cannon Place.” The Cannons sold it in 1919 to Cochran, Simpson, and Tucker. In 1935, the badly deteriorating house was purchased and lovingly restored by the Neely Grants of Memphis. Built for the belle of Memphis, Ann Elizabeth Park, the house owes its continued existence to Memphians. In the past forty years, it has changed hands a number of times, the owners nearly always being Memphis people – the William Walkers, the artist Charles Inzer, and, for the past decade, the Alfred Cowles family.

Summer Trees has a long history of gracious country living, and even of pomp and pageantry. In 1869, the “Wash Taylor place” was the scene of the largest tournaments ever held in the county, attended by between seven and eight hundred people (See South Reporter, 28 Apr 1932). The spectacular hall was made for dancing, and over the years grand entertainments have been given in the house. Miss Martha Moseley, who danced there in the 1910s to the music of W.C. Handy, remembers that her mother also attended her first ball there during the Rand occupancy in the 1870s.

We are fortunate that this landmark survives, treasured evidence of our county's past. Perhaps now, over forty years after the house was saved from destruction, we can begin to remove it from the realm of legend and place it against the proper backdrop of history.

Note: Tom C. Stewart; Norman Chronister of the Department of Archives and History; and W.P. Nicholson, Jr., a Taylor descendant, have all aided me in research for this essay.

This Page Was Last Updated